“I don’t know how it is I am alive.”

Our hired-on-the-spot guide at the S-21 Prison in Phnom Penh, Cambodia told us with thickly-accented English. A survivor. A once 10-year-old girl, now woman, told us her story inextricably mixed with the history and horrors of S-21. Her story of being forced away from her home, her city, losing her mother, her sisters, brothers, and father and not being told why. Her story of being a child-pawn in the horrific plan of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge regime to build a Maoist, peasant-dominated agrarian cooperative enforced by starvation, torture, and blind mass murder.

Marianna and I arrived in Phnom Penh, grateful to leave Laos. Jumping on a tuk-tuk after enjoying the novel luxury of traveling by air, we were greeted by the smiles of Cambodian drivers weaving in, around, past, and across us as we sat in a tuk tuk chugging through the vibrant city. We soaked in the smells and colorful sights of the market, drank in the city views and breeze of the Mekong, and feasted on flavorful cambodian dishes. Woven in the threads of this beautiful country, however, are not-so-distant painful memories of the genocide that killed 3 million people, or one-third of Cambodia’s population.

Shamefully, this is a history that I as an American only recently learned about. Shamefully, I am from a country that recognized this killing-regime as legitimate both while they were murdering their own people and after they were defeated by the communist Vietnamese in the 70s. It is a shameful story where the US is not the hero. I wanted to learn more about this story, about the people who suffered, who died, who are now rebuilding. Moving through the killing fields and the S-21 Tuol Sleng Museum was incredibly humbling.

The day was heavy.

The melodies and voices composed and spoken by genocide survivors echoed through my ears walking through the Killing Fields, transmitted through the audio guide handed to each visitor upon arrival. I had read hundreds of documents written by the Khmer Rouge in a class I had my last semester of law school. I was an intern with other students assigned with assisting the tribunal prosecuting the Khmer Rouge’s war crimes. I had seen various reports and documents recorded by the regime who, like the Nazis, meticulously documented the progress made towards achieving an agrarian society. Seeing this place, hearing these stories, standing upon the ground where many lined up 40 years ago to be killed and thrown into pits, made all these documents come to life. It made Cambodia’s past impossible to swallow.

The killing fields is the place victims were brought to be killed. The field is scattered with depressions in the soil, once mass graves. Women, children, and men were murdered with whatever cheap tool soldiers could find and then thrown into the graves. Still today, when it rains, pieces of cloth or human bone emerge from the ground, ghostly reminders of what happened here.

Slowly making my way through the field, lead by the somber voice of the audio guide echoing through the plastic headphones on my head, I stopped at one particular tree. It stood, rooted to a particularly remarkable horror. It is the baby-killing tree. Soldiers flung babies against its hard bark, murdering them before throwing their small bodies into graves. Pol Pot said in order to eliminate the traitor, even the root must be removed – which meant killing the children of “traitors.”

It was silent in the field. Visitors to the museum moved slowly, trying to make sense and understand what had happened there. The graves, marked by wooden signs and fences, were decorated with tourists’ bracelets knotted around the wooden poles, making some sort of offering in memory of the many lives that were haphazardly thrown in these pits.

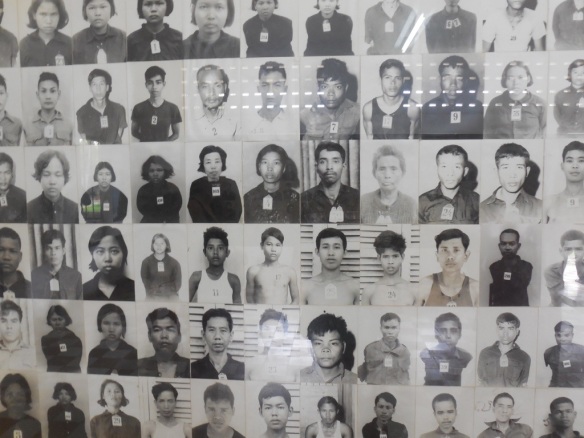

After leaving the killing field, worn and stunned by what we had learned, heard, and felt, we headed to Toul Sleng Museum. Here, the Khmer Rough transformed an old high school into a prison and torture chamber named S-21. Seven prisoners survived to tell the details of this hell after the Vietnamese overtook Phnom Penh, so the stories of what happened here are well-known. Rooms with metal beds and torture devices decorated the first floor of the prison. The faces of the prisoners housed within its walls, both dead and alive, are displayed on the walls. Each man, woman and child killed in S-21 were photographed as proof that no one, no one escaped. One room, holding individual cells divided by brick walls, had a pool of dried blood on the floor from its last inhabitant.

Our guide, a survivor of this genocide, told us the gory and horrific details of S-21 with a stoic face. We listened, took it in, and asked for her story. Her story of being 10 years old, forced to work in a child’s work camp, and starved. After the Vietnamese came, when Non was 13 years old, weighing only 15 kilos, she walked back into Phnom Penh, looking for her family. This resourceful brave girl found her mother amongst the city’s ruins and began to rebuild her life.

Non still smiled at us when we left. She learned English so that she could become a guide. She shares her story and the story of her country’s history every day, multiple times a day, to tourists.

She is resilient. Her people are resilient. And I, I was humbled by this story of resiliency, of the human spirit, of survival. In the wake of these recent horrors, in Cambodia, the people smile. They smile defiant, resilient, determined, brave smiles.